Our Curious Brain

Did you ever wonder how our brain sorts all the information that comes at us every second of the day? Like a good manager, the brain prioritizes incoming information and deals with what it believes to be the most urgent tasks, putting others on the back burner until the most pressing task is dealt with.

Our brain’s sole purpose is to keep us safe. If there is a change to our environment, our senses alert the brain to that change, and we are compelled to pay attention to the change to see if there is a threat to our safety and survival. Any change in the status quo will set off alarm bells and we will be put on alert until we either determine that the change is non-threatening, or we deal with the threat by fighting it or running from it.

In the case of sound, it is not just the awareness of new or unfamiliar sounds that triggers us to investigate, it is the change in the sound environment that is alerting to our brain. That means even the removal of an expected sound can catch our attention and cause us to focus on that change. Someone who lives in an urban setting where there may be traffic noise throughout the night, or perhaps trains pass at regular intervals, may become unaware of these sounds. Their brains habituate to the expected sounds so that other information can be attended to. If that person was to go camping or visit a friend in a rural setting, they may have problems falling asleep because it is too quiet. Their brains would alert them to the change in the sound environment so that the change can be investigated. The phrase ‘deafening silence’ comes to mind. For those who are used to a certain amount of environmental noise, the change to an environment of little or no sound can be alerting and can even cause anxiety or a feeling of unease.

There have been a handful of times in history when Niagara Falls has nearly completely frozen over. Those who lived close to the falls were woken by the eerie silence or had problems falling asleep. Their brains had accommodated to the steady roar of the falls. When that roar was reduced to a trickle, they were alerted to the absence of the familiar sound.

Quiet sounds can be as alerting as loud sounds if they carry emotional weight. A new parent can be woken from a sound sleep if their new baby starts to whimper in a room down the hall. Although the physical volume of the sound is very quiet, the impact of sound is significant as it triggers an emotional response tied to the meaning given to the sound - thoughts of love and protection, or possibly aggravation and frustration. It is the thought about the sound that results in the emotional response to the situation. If the parent is sleep-deprived and must get up to go to work in the morning, the thoughts about being woken in the night will be different than if the parent is able to sleep in the following morning. The sound of the baby is not what determines the mood of the parent, bur rather the meaning and thoughts around the baby whimpering.

Our own names have strong emotional weight for us and those who know us. If you are at a large gathering where everyone is talking, you may barely be able to hear the person standing directly in front of you, yet when someone across the room mentions your name, you may hear it clearly above all the chatter. The reason for this is that your name has significant emotional weight. You have heard your name being spoken since infancy and it has been imprinted in your brain. Your name was not being spoken louder than the rest of the conversation in the room, but it popped out above the rest because it has been assigned importance and therefore your brain will be alerted and will hear it above sounds in the room that are as loud or louder.

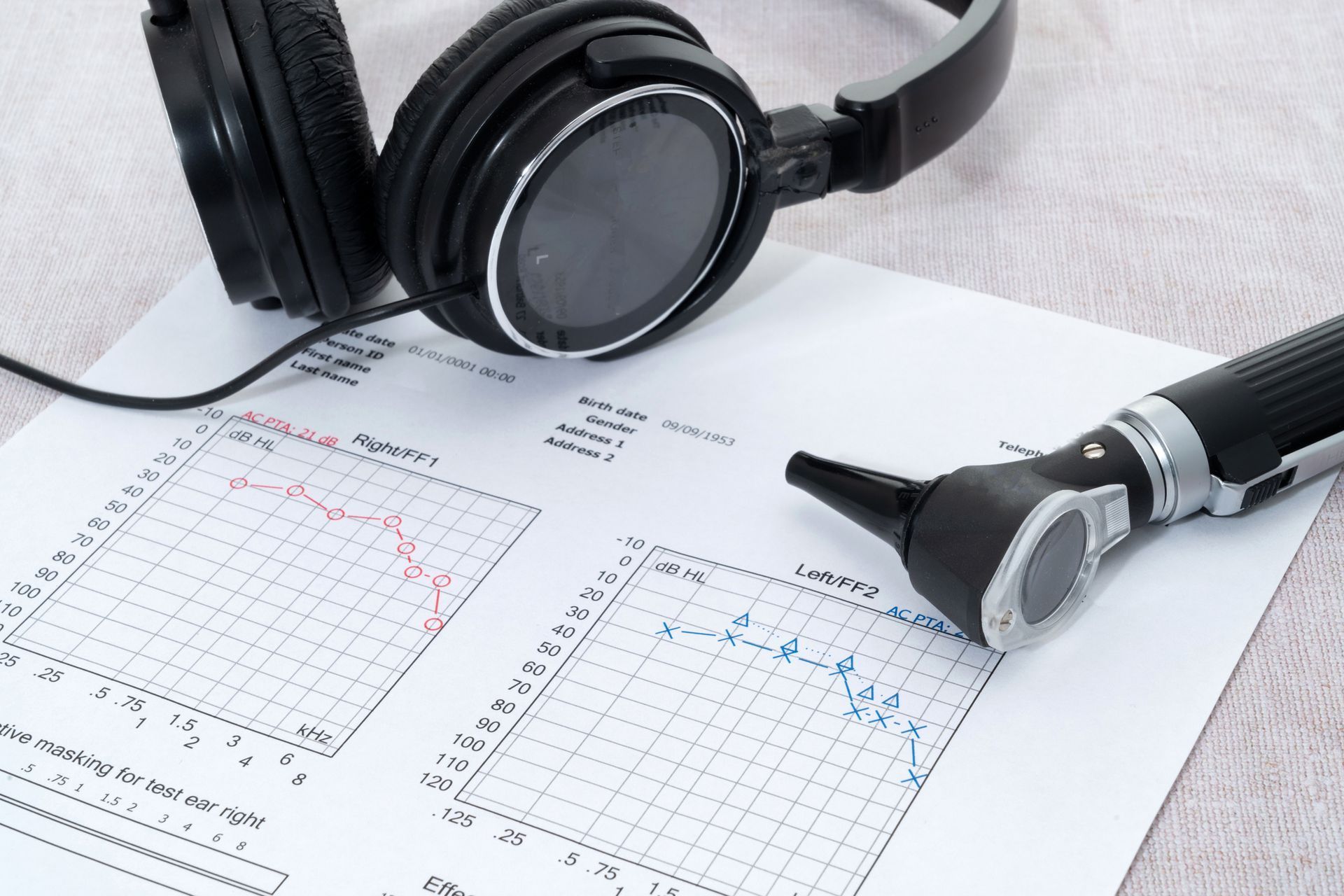

These examples demonstrate that the measured volume of a given sound is not as important as the meaning that we give the sound, whether positive or negative. We can measure the volume of a person’s tinnitus in the sound booth by increasing the volume of a tone or hiss that approximates the frequency of the tinnitus, and asking the person to indicate when the volume of the tinnitus is equal to the volume of the sound we are delivering through the earphones. While those with bothersome tinnitus often describe the tinnitus as being as loud as a siren or jet engine, they match the volume of their tinnitus to a sound that is very quiet, often not much louder than the quietest sound that person can detect at the same pitch. Why is this? Our distress from the tinnitus is related to the thoughts we have about the tinnitus, the meaning we give it and the focus we place on it. A quiet sound can have a big impact. Our brain has been trained to be on high alert to monitor this intruder we call tinnitus, and we are bothered by it because we focus on it over everything else. You may claim that you are unable to turn your focus away from the tinnitus, but there are techniques to retrain your brain to put the tinnitus in its place so that it has no impact on your quality of life. Most people that have tinnitus experience no impact from it. They have habituated, and you can too. Find an audiologist who can help you retrain your brain to filter out the tinnitus so that it has little to no impact on your quality of life.

Recent Posts